![]()

Charles Darrow' "Monopoly" patent diagram

Looking at the markings on a popular, contemporary board game we’ve played a number of times, be it as simple as tic-tac-toe or as complicated as Monopoly, we see the rules written across the board in the signs and symbols as clearly as if they were written out in our native language. The artwork and design, whether simple or complex, is not as much an attractive thing to look at, as a secret regime of signs. They are grids of pathways that we have walked countless times in our plotting minds. They are not matrices of open space, so much as dimensions of future moves–the windpipe on the neck of fate, around which we’ll wrap our fingers. They are diagrams of conflicts and bargainings, taxonomies of tactical encounter and cooperative maneuver. In perhaps a similar spirit to the way that Westerners referred to their Colonialist expansions as “The Great Game”, the game board in the mind of a concentrating player is that sigil of one’s will made totally manifest without inhibition. The boundaries of the game are the entirety of one’s existence, and nothing matters outside of those rules. Ethics, morals, and other idealistic limiting conditions bring nothing to bear on the universe of the game, for the absence of reward for ulterior morality within the game, leaves the lack thereof squarely on the table. Or as a fellow player once said when caught stealing from the Monopoly bank, “In Monopoly, cheating is part of the rules.”

And hopefully only within those rules. So many of our games are simulations of cutthroatedness, hording, manipulation, and domination. Perhaps that is why we allow ourselves the unrestrained cruelty of the rules of games. In everyday life we are forced to justify, to defend, to balance end for means so often, that sometimes it would be nice just to dispense with the pleasantries, and just play the game. Human culture is a culture of games, and despite our willingness to treat many facets of real life as a game sequestered from other systems of valuation, we still invent new, tiny squares into which cast lots and move pawns.

![]()

Xiangqi game set

But looking at the history of games not quite as recognizable as those on our closet shelves today, our games are still often analogs for familiar situations of life’s unruledness. War is naturally a common theme, in the case of

Chatrang or Shatranj, the Indo/Arabic precursor to European Chess (dating from the 7th Century AD) and

Xiangxi, also known as Chinese Chess (from the 6th Century AD). But though the pieces and board in Xiangxi describe various military units and geography, a different reading of the name can translate it as “Constallation Game”, and the river that runs through the center of the board can be taken as the Milky Way. The symbolic value of games is almost always multifaceted.

The linearized conflicts of board games might also stand for our more abstract duels of logic, such as in the case of Go (from the 6th Century BC), or the Egyptian game Tâb, and its similar Scandanavian cousins Daldøs and Sáhkku (the latter two theorized as coming from Africa in 1800 AD at the latest, though no one is really sure). Let the conflict take what specific form it might in the real world, here, it is a matter of tile against tile, marker against marker. A win is definable, a loser is inexorable.

![]()

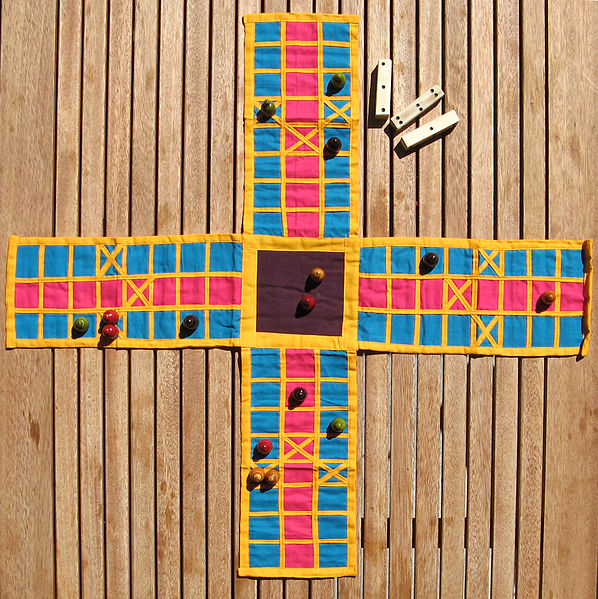

Pachisi game set

No matter how abstract, board games like these have a huge social importance.

Yut (dating to the 1st Century AD), A Korean game with very similar throwing sticks to Tâb, is traditionally played on the Thanksgiving holiday with a crowd gathering around the board.

Pachisi and Chaupur (evidence show this game played as early as the 16th Century AD but it may go back much further), two Indian game variations simplified and marketed in the West as “Parcheesi” were played by rulers on a large scale, using servants as piece markers in courtyards built into game boards. What the wins and losses stand for in this case is not as important as the way in which the players stand to face each other. One might say the same thing for chess tournaments between Soviet and United States players in the late 20th Century, or matches between humans and computers today.

![]()

terracotta statue of Xochipilli

That board games might have a religious significance overlaying the game play should surprise no one.

Patolli, an Aztec game with variations dating back to the Teotihuacanos (in the 2nd Century BC) had a core feature of gambling, but always included the god

Xochipilli in on the action. If a certain space on the board was landed upon, a player had to give up one of the wagered items to this god of art, games, beauty, dance, flowers, and song, patron of homosexuality and

entheogens. While there is nothing not serious about gambling, The Egyptian game of

Senet (dating all the way back to at least the 31st Century BC) was perhaps even more important, being a gamified metaphor for the journey to the underworld.

![]()

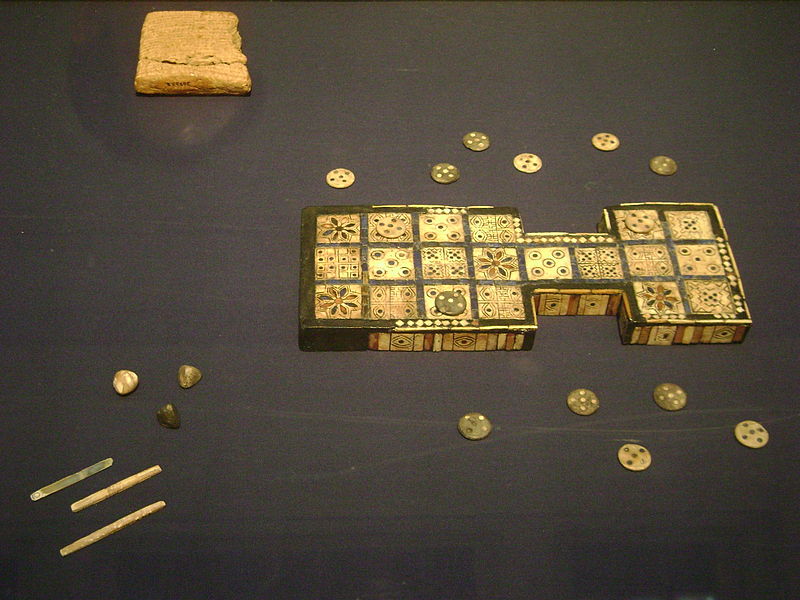

The Royal Game of Ur

Senet is a game so old, that we have forgotten how to play. Historians know what pieces were used, and have made conjectures about how it might have been played. Contemporary game manufacturers have gone so far as to sell copies of the games with rules derived from historians’ theories, but even the

game players themselves cannot agree on the rules, and choose their own variation as they go.

Mehen is another Egyptian game that we know of but have lost–in this case, historians aren’t even sure of the correct number of pieces to use. The so-called

Royal Game of Ur is a game that remains mysterious as well. Despite some recovered game boards with beautifully preserved construction, and even a cuneiform tablet describing the game play, not all the details are known, and gamers today have to make do with their own creativity.

![]()

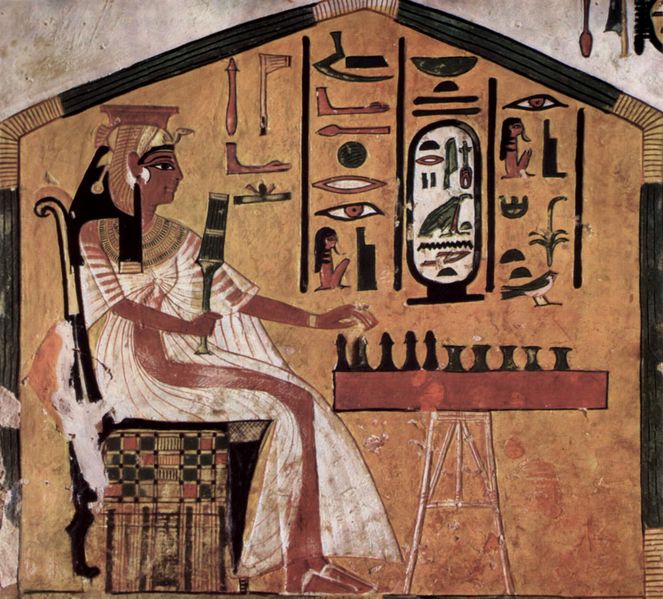

Nefertari, playing Senet

Perhaps at the time when the boards of these games would have been common symbols for anyone in the culture, no one thought to preserve a detailed description of the rules. For the people of Ancient Egypt, just as when we gaze upon a Monopoly board, the rules projected up from the game material so obviously. For players of Senet, a game that described a very important aspect of their religion, to explain how the game worked to anyone but a child might seem as odd as explaining us having to explain how money and rent work. The strict universe of rules we inscribe in our games is not just an abstract program, but it’s a little bit of ourselves. Viewed this way, it seems almost fitting that an ancient culture’s game of the dead is a game we don’t know how to play. And yet we try anyway, adapting it for our own amusement; every game listed here, with the exception of Mehen, is for sale and played by gamers today. Some are still incredibly popular, others are merely curiosities. Perhaps it is a fatalistic end for the forgotten games, important in their times, to become no more that just another diversion today. And even those that are popular now–who can say what will happen to them in another thousand years? But then, human history always was a game rife with pathos.